MMA fighter practices punching drills in his garage in Pembroke Pines, FL.

One, Two, One, Two. Jab, Cross. Knee. One, Two. Kick. It’s 4:30 P.M. and the afternoon light is shining through his garage. Amateur mixed martial arts fighter Ryan “Third Street Savage” Kuse is working on what he believes led to his recent loss: his lack of stamina during a long bout. It was a fight he was winning but one in which he made one mistake after he got tired. One punch and it was over. It’s a loss that has momentarily halted his young career.

“I think the scariest part about this is that once you step into the octagon, you don’t know what is going to happen next,” says Ryan, who started his amateur career five years ago. “You don’t know if he’s going to come out alive, you don’t know if you’re going to come out alive.” A grueling sport, mixed martial arts (MMA) is a full-contact combat sport in which fighters are allowed to use a variety of fighting techniques - both striking and grappling - as they attempt to defeat their opponents. At the amateur level, the sport can be much more cruel. The lack of pay, the lack of resources, and the lack of control over one’s future make it difficult for young fighters pursuing their dreams.

The amateur level of the sport consists of a wide range of fighters with different circumstances. Some fighters have families and full-time jobs and can only practice a few hours a week. Other fighters, like 25-year-old Ryan Kuse, have decided to make training their sole priority - practicing 14 hours a day for months before their fight, hoping they can secure a win every time they step in the octagon. In mixed martial arts, it is important for a fighter to know and perfect a wide range of techniques from different disciplines. The wrestling, the jiu-jitsu, and the boxing, all have to be on par if a fighter wants to have a winning chance during the fight.

Ryan trains 14 hours a day, 6 days a week to make sure he’s ready for his next fight.

Ryan is able to train all day and pay several coaches by living with his mother and cutting down on his cost of living. “People think I am a bum for living with my mom and training full time but they don’t see the vision,” says Kuse. “I found my passion, after years, I found what I like to do.” His mom, Lisa Kuse, supported him from day one. “All we can do is be here for him and be supportive. I think him being here and not having to worry about the other little things in life that get caught in the way, allows him to focus on the things he really wants to do.”

Ryan poses with a Lamborghini that a new sponsor lent to the gym where he trains. The sponsorship will allow him to choose any car he wants for fight days.

Ryan stays after practice to help clean the gym.

The life of an amateur MMA athlete that competes in local promotions or events is paradoxical. On one hand, fighters must train and prepare for fights for which they make zero income. If they don’t work, as is the case with Ryan, they are not making money and training is costly. On the other hand, if they are able to secure sponsors, they get treated, for short periods of time, with a life of luxury. Ryan, for example, has several sponsors including an exotic car rental company. On fight nights, they offer him a sports car of his choosing to drive to a fight. He explains that many of these sponsors are fans of the sport and wealthy people who wish they, themselves, could fight. Though he says he would obviously rather get paid, he understands that this is just part of the journey.

Once an amateur fighter decides to make the jump to the professional realm, their life does not change much in terms of finances early on. First, a fighter usually signs with a promoter that can find them higher paying sponsors and lucrative fights. Promoters usually take anywhere from 10 to 20 percent of the contract the fighter signs, which ranges anywhere from $500 to $2,000 dollars at the beginning of their career. Many fighters, like Ryan, heavily rely on the contributions of their sponsors while they fight in the lower paying “feeder promotions,” or the events that serve as a steppingstone to bigger promotions such as the Ultimate Fighting Championship (UFC). This is where fighters envision themselves, where most make more than $100,000 dollars a year with the top-earner making $9.5 million. It takes a while to get to the pinnacle, however, and fighters must be strategic in the fights they accept and make sure they win most of their fights early on.

To try to compensate for the lack of revenue, Ryan creates his own merchandise and sells tickets to his fights. Weeks before the event, he produces shirts and ski masks that he’ll sell to supporters. He also advertises his fights to try to make as much commission from ticket sales as possible. During his last fight, he says he made about $5,000 dollars from the outside hustle. While this may not seem like the ideal conditions in the pursuit of a dream, it is what Ryan must do to make any cash.

Ryan recovers from intense training through massages and “cupping,” a therapy that involves placing cups on the skin to create suction.

The suction is said to facilitate healing with increased blood flow.

Ryan’s comeback fight was scheduled for February 9th, 2020 in South Florida against Colombia’s #1 ranked MMA fighter. He was going be the main event. But after training for five weeks, he was notified a week prior to the fight that his Colombian opponent was unable to secure a visa and would not be fighting. He was offered another opponent - one that was not highly ranked in the state - and he chose to opt out of fighting. “As a fighter, your body only has a limited number of punches it can take, so many weight cuts you can go through, so many fight camps, and as years go by, everything diminishes slowly. I want to preserve my body for the right moments and use everything I got when it’s worth it.” In this case, the recognition he would get from winning the fight was not worth the energy and resources he was going to spend preparing for it. This is the everlasting struggle of an amateur MMA fighter. They’re only in control of their dedication to the sport and not much else. In this case, all of the time and resources Ryan employed to make sure he had a chance of winning were in vain.

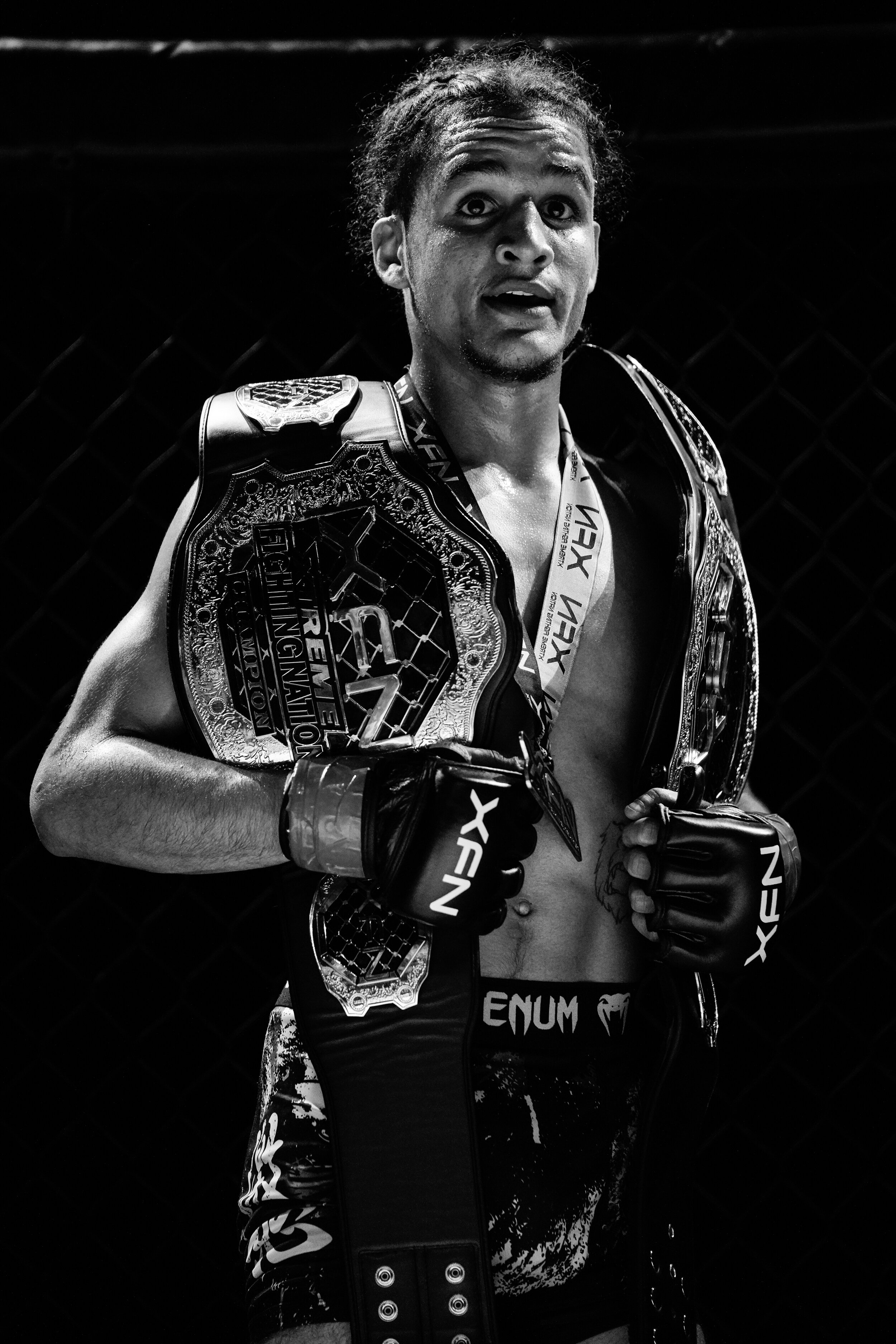

Images from Xtreme Fighting Nation (XFN) 27 on February 9, 2020. Ryan was supposed to be the main fight at this event but his fight was canceled after his Colombian opponent could not secure a visa.

A few weeks after his postponed fight, Ryan was back at boxing practice getting boxing rounds in. Despite not having a fight scheduled, he was working on new techniques. His boxing coach is training him intensely, allowing him to get in the ring with a couple of Ultimate Fighting Championship (UFC) fighters that practice at the gym. After a few exhausting rounds, Coach Kevin Gleason yells at Ryan to come out the ring. He was impressed with what he had seen. “I think you’re pro ready, Ryan,” he says. Ryan had been hesitant about turning pro up to this point because it’s the biggest step one can take as a fighter. As he explains, “imagine you want to be a doctor and you get one F, that can determine if you become a doctor or not. That’s the same thing with going pro. If I turn pro and I lose once, that can make me lose my chances of getting to the UFC. That’s why I’ve been nervous.”

The next day, Ryan decided to turn pro. His debut was scheduled for March 17th at the Hard Rock Casino in Miami, FL. Again, after training for a couple of weeks, his career was once more put on hold after the Covid-19 global pandemic forced events around the world to be canceled. Ryan is undeterred. “The way I’m training, if I don't make it next year at 26, I’ll make it at 27. If I don’t make it at 27, I’ll make it at 30. If I don't make it at 30, I’ll make it at 33. It doesn’t matter what happens. I am going to make it.”

“The way I’m training, if I don’t make it next year at 26, I’ll make it at 27. If I don’t make it at 27, I’ll make it at 30. If I don’t make it at 30, I’ll make it at 33. It doesn’t matter what happens. I am going to make it.”

Post Interview with Ryan “Third Street Savage” Kuse

“The scariest part, is that you’re walking into the unknown.” In January, I started filming Ryan “Third Street Savage” Kuse’s journey as he pursued his goal of making it to the Ultimate Fighting Championship (UFC). The path of an amateur MMA fighter has many obstacles, many of which, are out of their control. From the time they decide to become a fighter, to when they sign up for their next fight, to when they step in the ring, there is always the ‘unknown.’ Despite this, Ryan is resolute in accomplishing his dream and becoming the best fighter he can be. Join Ryan and me this Saturday live through YouTube as we talk about his career, this short doc, and what’s next after we get through this pandemic.